SOMA

Frictional's Sci-Fi, Existential-Horror Masterpiece

Introduction

I started out my Amnesia: The Bunker review explaining how my taste in horror games had shifted over the years and how survival horror was the in-vogue genre for me. In 2021 I played or replayed nearly every main line Resident Evil game. Then in 2023, Signalis and more importantly The Bunker solidified my love for the genre outside of the RE franchise. If you’ve been following my writing, you'll know I recently dove into Frictional Games' back-catalog and played the Penumbra games. I was pleasantly surprised! But if you read until the end of that article, you’ll also know that I was blown away by how utterly garbage Amnesia: Rebirth was. I was so soured by the experience that I wrote up a hasty bonus section for the Penumbra article simply bashing the game. At the end of the day though, I didn’t want to leave Frictional Games' catalog on such a poor note. And then a random Steam user commented on my Rebirth review...

For context, I had written that Rebirth felt incredibly 'on-rails' and then finished by remarking that maybe I should replay SOMA. My immediate, gut reaction to the comment was that it was misguided to say the least. At the same time, I had not played SOMA in nearly eight years. I recalled SOMA being a linear, narrative-driven, horror game but also knew I absolutely loved it. This left me wondering, did my taste really shift that much over the years? Are Frictional's older horror games all 'on-rails'? Can I better define this awful 'on-rails' feeling I got from Rebirth? All this compelled me to replay SOMA.

The answer to the first question is easy to answer. No, my taste only grew to include survival horror and now replaying SOMA I can confirm its greatness stands the test of time. Let's get into why I think SOMA is a masterpiece and perhaps answer those other questions along the way. To accomplish this, we are going to dive into a detailed breakdown of a one hour-long segment of the game. But first, for the uninitiated, here’s a quick introduction to SOMA.

What is SOMA?

SOMA at a most basic level is a first-person sci-fi horror game. I describe it as heavily narrative driven while having a minimalist approach toward gameplay mechanics and systems. The game is set in an underwater research facility that has befallen a mysterious fate. In your time with SOMA the player participates in a uniquely riveting narrative, explores many derelict sites, solves immersive puzzles, makes reality-questioning choices, and carefully chooses how to interact with those who remain “alive” at the bottom of the ocean. At its core, SOMA is an immersive, thoughtful experience that invites the player to engage with its detailed world in the aforementioned ways. The horror is derived from the player being engaged in the narrative and being in touch with what is going on in their environment. SOMA is not about complex gameplay systems; the goal is not to win. SOMA is not a jump-scare horror game; the goal is not to startle the player.

Okay, so that’s a little bit of expectation setting out of the way, now let’s briefly introduce some names and places. This is so that when I start talking about them later, everyone at least has a surface level understanding, nothing more. So, in SOMA you play as Simon, a run-of-the-mill, middle-aged Toronto native who happens to wake up at the bottom of the ocean. We get a brief view of Simon’s life in Toronto, playing out his normal life up until he receives a brain scan. The next thing you know, we find ourselves in PATHOS-II, a research and mining complex that is spread across multiple sites on the ocean floor. It is quickly apparent that PATHOS-II is not in the best condition. Crews have abandoned their posts, site systems have been either neglected or forced offline, and danger lurks in the form of deranged robots, at least that’s what they seem like. You’re first goal is to survive, hopefully come in contact with another human, and figure out what is going on. If that’s enough to pique your interest, cool, check out SOMA. If not, I’ll give a little more info, but this could be considered slight spoiler material.

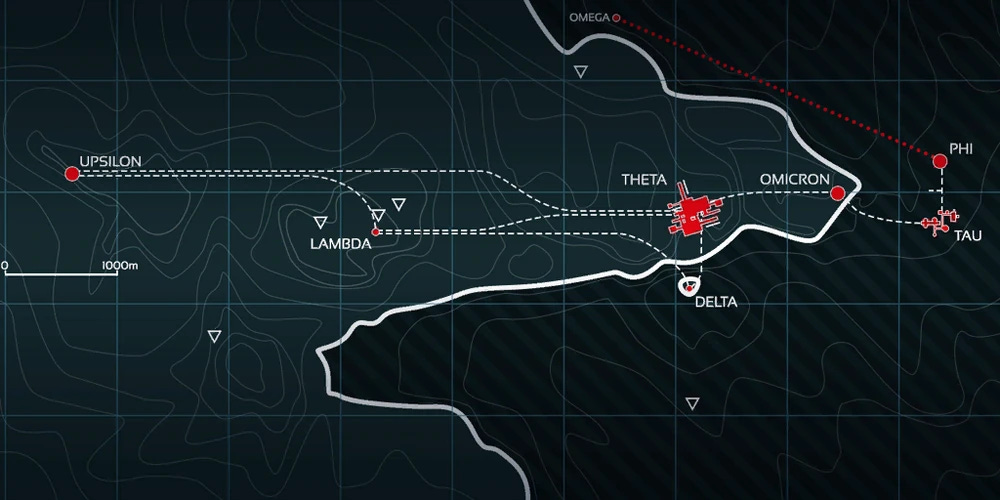

In our exploration of Site Upsilon (where we woke up), we make contact with seemingly another human, Catherine Chun. Through conversations with Catherine we have some fairly significant revelations: we are no longer in our human body, it is the future, the earth was hit with an asteroid, it is unknown if human life as we know it remains, and an AI warden known as the WAU has gone rogue throughout the facility. The staff of PATHOS-II survived for a time and Catherine herself actually launched a project to provide humanity one flickering light of hope. Her idea, known as the Ark Project, was to transfer staff members brain scans into a digital environment and launch the hardware into space. This would preserve at least an aspect of humanity and give some hope for the future. However, the Ark Project failed at some point and when we find Catherine, it’s actually just her brain scan in a disabled robot laying on the floor. She asks Simon to attempt to complete the Ark Project’s mission and give humanity as chance amongst the stars. Since the Ark Project is also seemingly Simon’s only chance not to spend eternity in hell at the bottom of the ocean, we agree to help Catherine. This sets us on a mission that takes us through several PATHOS-II sites in an attempt to reach the Omega space gun located in the abyss. I’ll leave the introduction at that. Now you pretty much know the trajectory for the game and the names and places involved. Check out the video linked below and let’s get into the breakdown.

A Game Design Breakdown

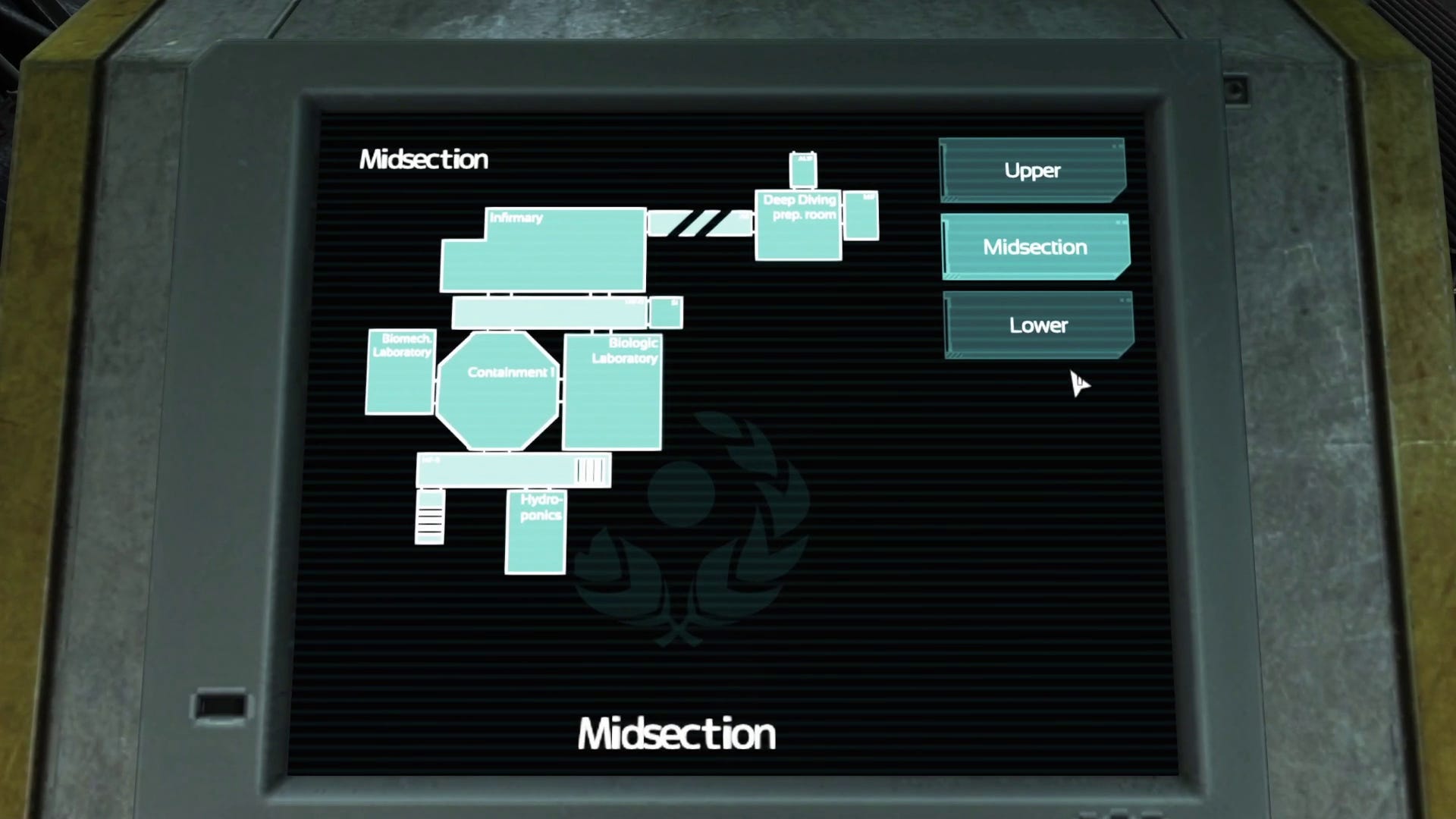

The video is a gameplay segment showcasing exploration of Site Omicron. Added are annotations that represent my own thoughts during gameplay. This is done to convey how I’m engaging with SOMA. The video is also a framework for me to dive into further details on a bunch of subjects. In the following sections I will be linking the video, timestamped to the relevant area. Omicron is an excellent microcosm of what SOMA does really well. While my review/breakdown is focused on this one particular site, know that at least three other sites: Upsilon, Theta, and Tau are of similar scope and quality. We reach Omicron approximately 75% of the way through the game, so spoilers ahead.

The Setup - A Detailed, F(r)ictional World

At Theta, Simon and Catherine discovered that the Dunbat, the only vessel capable of traversing the abyss, was corrupted by the WAU. Their final resort is to use the Abyss Climber Rig, essentially an elevator that extends to the abyss floor. The ACR is located at Site Omicron right at the edge of the abyss. Catherine explains that we’ll need to hope there is a power suit there so that we can withstand the pressures of the abyss and carry on with our objective.

I appreciate the lengths the development team went through to make PATHOS-II feel like a real location. Throughout the game, you are given context to current and future locations in the game world. Whether that be a geographical map or Catherine describing a place more qualitatively, you start to develop a sense of what these places are before you’re even there. Omicron for instance always felt like the end of the line, a final way point before plunging into the oppressive depths of the ocean. This version of Catherine doesn’t even seem to have been to Omicron before. Stationed at Theta, Catherine had only heard stories of Omicron. When telling Simon about the abyss climber in game she says: “It’s like an elevator which supposedly reaches all the way down into the abyss”. Parts of PATHOS-II have become mythologized by the staff, alluding to lives and conversations they had in a previous life. This is nice world-building, it sets the tone for you, the player.

After experiencing the horrors of Site Theta, you hope for relief at Omicron but know that is unlikely to be found. Omicron teeters on the edge of the plateau. The climber rig stretches out ominously over the abyss. The site is also on quarantine lockdown. It’s difficult to be hopeful when you find the last survivors of Theta laying around outside Omicron’s gates. They couldn’t find a way past the lockdown, they ran out of oxygen and suffocated. Tapping into the Theta staffs blackboxes (I’ll get into this in the next section) we can relive the final moments of their lives. Through this we can piece together who these people were and think back to our own time at Theta. We can remember seeing their living quarters, seeing traces of their narrow escape, finding those that were left behind, and realize the sacrifices that were made. In SOMA, at PATHOS-II, it feels like everyone has a name, everyone had role. Slumped against a substation anchor point, we find Peter Strasky, Theta dispatcher and friend of an important someone at Site Omicron.

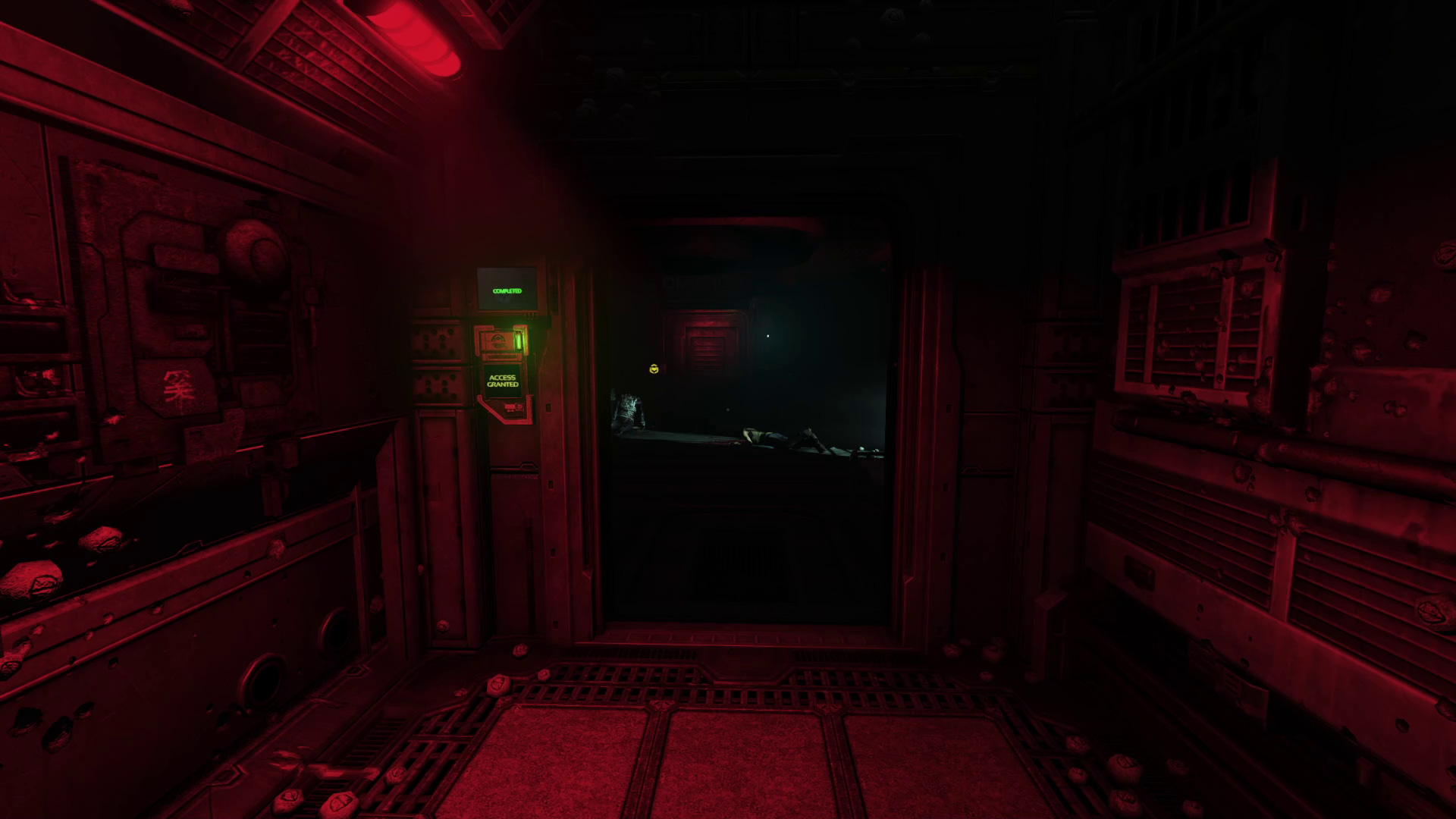

Simon, fortunately, does not suffer the same fate, someone or something wants us to come inside. A terminal in Omicron’s substation outside the station itself mysteriously displays the quarantine override code and we’re able to make our way inside…

The Arrival - Creating Direction and Intrigue During Gameplay

Timestamp - 1:28

SOMA is fantastic at clearly articulating objectives to the player in a diegetic way. I get into detail on that in the next section but mentioned it because Frictional are equally adept at introducing plot threads through environmental storytelling and in-gameplay scripted segments, never cutscenes. I’ve grown to appreciate that aspect about their games. The lack of cutscenes hearkens back to classics like Half-Life 2. The flow achieved when everything occurs in real-time from your point of view is something I am really drawn to and engaged by, so let’s get into more specifics.

It’s very important to not strip control away from the player or abuse the “during gameplay cutscenes”. Take Metro Exodus for example, it’s a game with really good gameplay stitched together with “interactive cutscenes” from the first-person perspective. The problem with these “cutscenes” are that while you can look around and occasionally interact with something, you usually cannot move (and if you can you’ll be stuck in the mud on the lowest gear), plus you definitely can’t look in your inventory or pull out your weapons. The result is that I feel like I’ve been put in a straitjacket, not good. The other big issue with the blending of gameplay and cutscenes can be seen on full display in the opening sequence of Resident Evil 3 Remake. In this case, it’s the splicing together of quick cutscenes with segments of restricted gameplay. Nemesis bursts through the wall in a cutscene, next you run down a hall only holding the run forward button, you escape and a little later you slowly walk up a street to the next cutscene. The result is that RE3R takes an hour to get off the ground and get to actual gameplay. As the plot, gameplay tutorial, and setting/characters all try to vie for the player’s attention at once, the intro becomes a sputtering, stop/start mess.

I describe all this to say I prefer SOMA’s approach. The story happens during and in amongst the gameplay. You are always in control, there’s never mixed messaging. This is why I really appreciate Catherine, both as a character and a gameplay mechanism. She is you’re only consistent form of “human” interaction and she’s also you’re navigational compass. After enduring the unknown horrors of the abyss, the player wants to just hangout by a computer terminal and talk to Catherine for a minute. The game doesn’t have to strip away control or force feed cutscenes for the player to stay with and talk to Catherine. It just happens because it’s what a human would do in this situation. I love that, the harmonious marriage of story and gameplay. With that being said, a distinct, concise cutscene can do a lot for a game. Think of the intro cinematic for Dark Souls. It sets the tone, give a synopsis of the world’s history, and foreshadows what’s in store for you, the player. I like it a lot, also I can easily skip it on a subsequent playthrough… Ok, enough on cutscenes, let’s get back to SOMA.

So back to the video, right when we step into Omicron we’re greeted by two dead crew members, two headless crew members. This is a twist that goes beyond just the gore of it all. All PATHOS-II staff have blackboxes embedded in their brains to monitor their vitals. In the rest of SOMA, when you investigate other sites, attempting to understand the final days of the inhabitants, a critical way you gather information is by listening to these blackboxes. That is how this detail goes beyond the gore, it actively puts you on the back-foot when it comes to understanding what happened here at Omicron. On the flip-side though it generates a whole lot of intrigue for you to dig into. Why is everyone missing their heads?

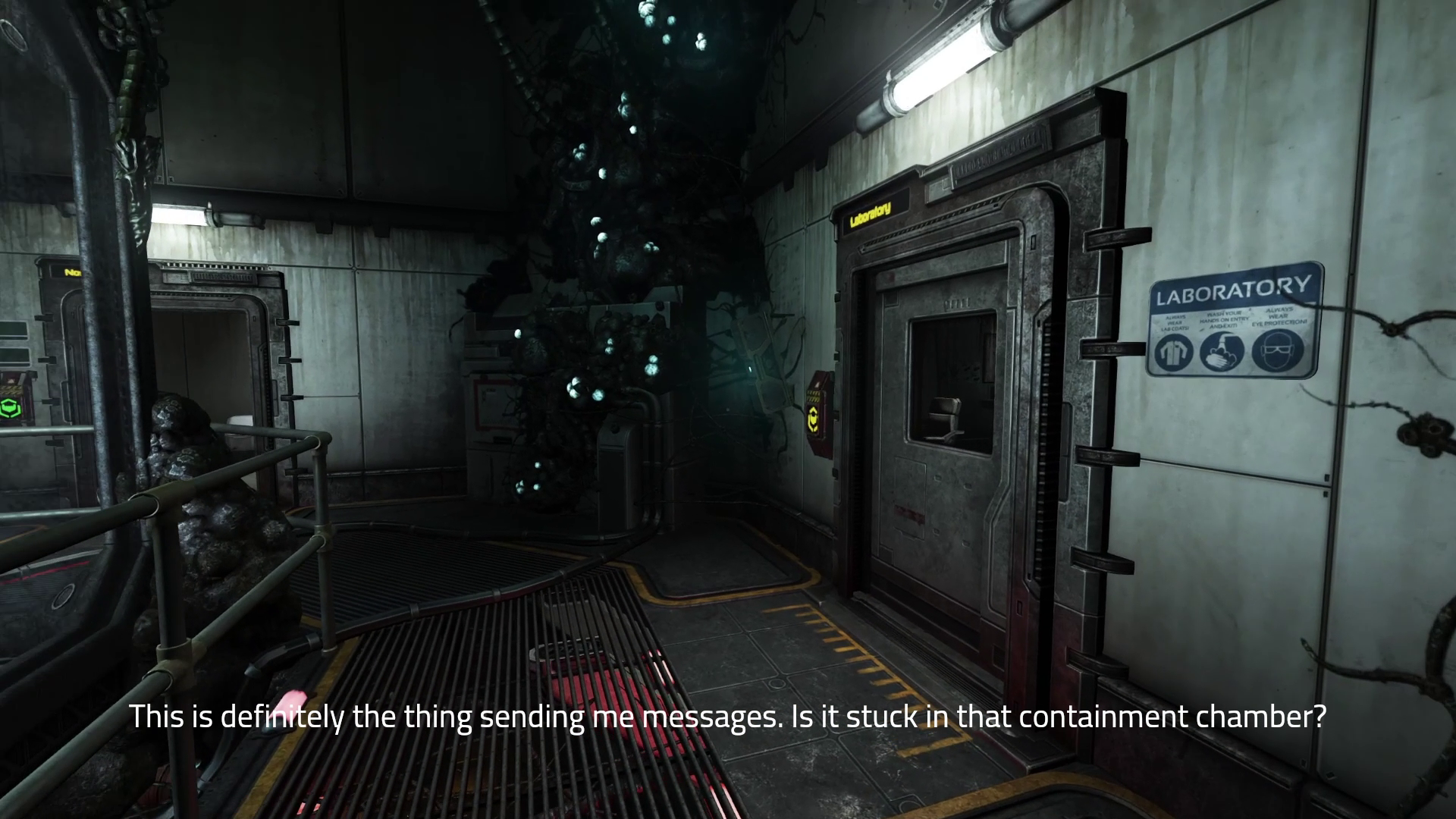

As you explore further into Omicron you come upon a centralized containment chamber. With a bit of a jump-scare, a creature appears in front of you in the chamber, utters the words: “You need to stop it.”, causes a whole lot of electromagnetic disturbance, then blinks out of existence. Outside of the general creepiness and shock factor, this is the first time seemingly one of the WAU’s monsters has attempted to interact with you. What is going on here? We now have two clear mysteries to attempt to understand while moving through Omicron.

The Dive Room - Clear Communication of Objectives and Sense of Progression

Timestamp - 4:53

Like I mentioned before, SOMA does a wonderful job of clearly communicating player objectives and goals without the use of any menus or HUD. Part of the reason is the setup I talked about earlier. Frictional created a detailed, logical world and introduced it to the player to set the stage for what’s to come. The large-scale stakes are pretty clear, and the geography of PATHOS-II has been laid out. This means the player understands the general weight of the current situation and has at least an abstract idea of where this journey might lead. The sum of this legwork that Frictional put into the setting is that when the player does move through the game world and story, there’s a true sense of progression. We’ll get back to this sense of progression in a bit, but first, how does SOMA handle the more moment-to-moment, small scale objectives?

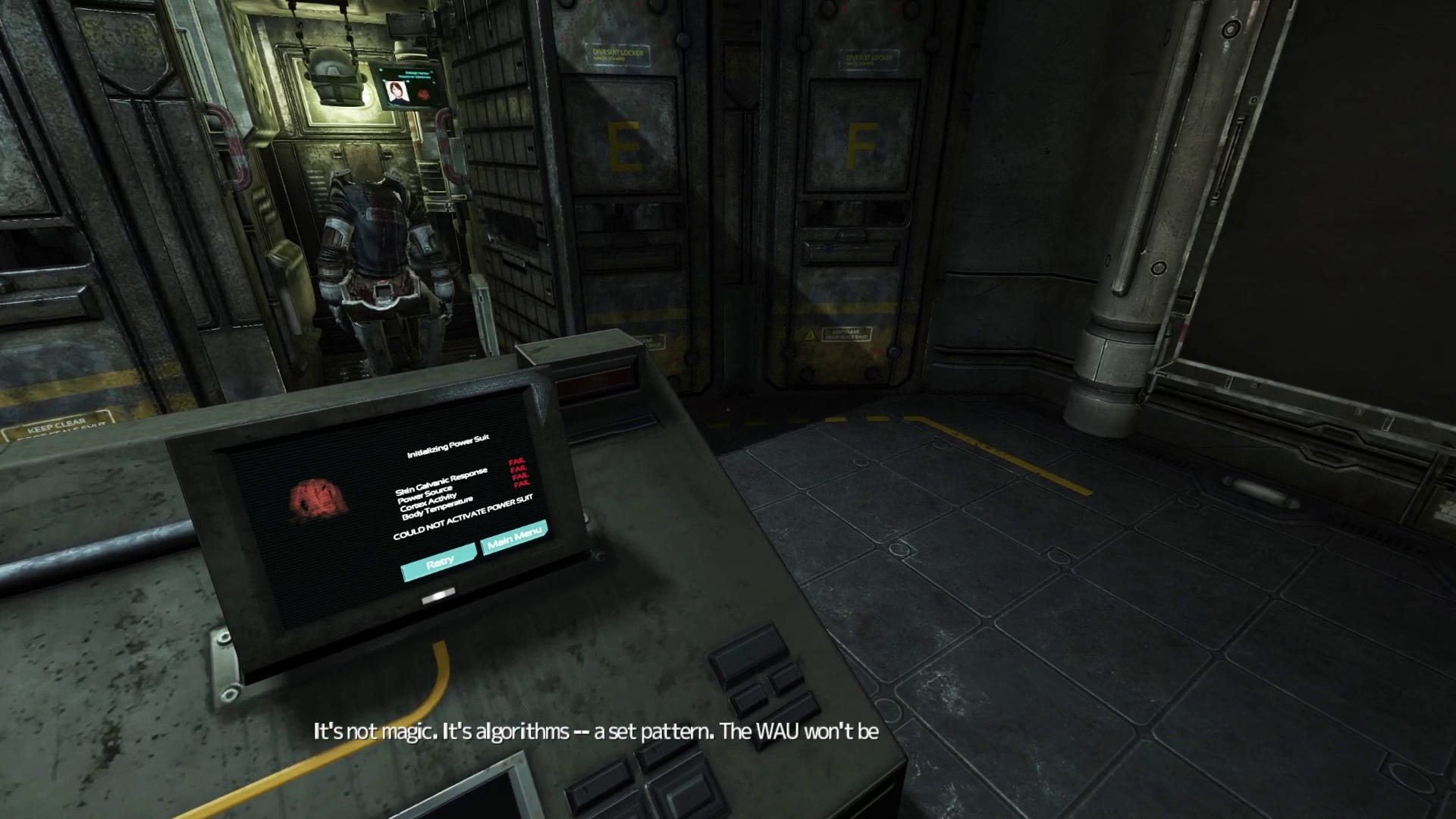

The answer to this is Catherine. Throughout your journey through PATHOS-II you’ll have an Omnitool embedded with a brain scan of Catherine Chun, a Systems Engineer at Theta and founder of the Ark Project, at your side. Catherine pops in and out of existence as you plug her in and out of terminals across PATHOS-II and gives you direction on both a macro and micro scale. At Site Omicron you find the Dive Room and plug Catherine. With her help you determine there’s one remaining power suit left. The hitch however is that you are already a robot in a diving suit and can’t throw the power suit over top. Since your physical being is intrinsically attached to your current suit, you have to prepare the power suit so that it accepts a brain scan transfer. With Catherine’s help, the suit terminal lays out exactly what tasks you need to complete. A battery pack to power the suit, a cortex chip to transfer your brain scan to, and some structure gel to bring it all together is your grocery list for Site Omicron. Now you’re set, you have a clear understanding of the big picture goal to find and launch the Ark and you have the short-term goal of finding these items.

So, let’s get back to the topic of progression. Bottom-line is that I think that a sense of meaningful progression is so key in these types of linear, narrative-driven games. SOMA got me thinking about this because typically my type of video game is more gameplay driven, I rarely play games for their narrative. So, SOMA left me questioning why it’s the exception.

In reading about SOMA’s development and reception through Frictional’s blog, I came across an article that struck a chord with me: Planning – The Core Reason Why Gameplay Feels Good, written by Thomas Grip, Co-Founder of Frictional Games. The thesis statement of the article revolves around how planning is a fundamental part of engaging gameplay. I agreed at least with this initial take and in reading further I found an excerpt of particular interest, as it compares Amnesia: The Dark Descent and SOMA:

Finally, I need to discuss what brought me into thinking about planning at all. It was when I started to compare SOMA to Amnesia: The Dark Descent. When designing SOMA it was really important for us to have as many interesting features as possible, and we wanted the player to have a lot of different things to do. I think it is safe to say that SOMA has a wider range of interactions and more variety than what Amnesia: The Dark Descent had. But despite this, a lot of people complained that SOMA was too much of a walking simulator. I can’t recall a single similar comment about Amnesia. Why was this so?

At first, I couldn’t really understand it, but then I started to outline the major differences between the games: Amnesia’s sanity system, The light/health resource management, Puzzles spread across hubs.

All of these things are directly connected with the player’s ability to plan. The sanity system means the player needs to think about what paths they take, whether they should look at monsters, and so forth. These are things the player needs to account for when they move through a level and provide a constant need to plan ahead.

The resource management system works in a similar fashion, as players need to think about when and how they use the resources they have available. It also adds another layer as it makes it more clear to the player what sort of items they will find around a map. When the player walks into a room and pulls out drawers this is not just an idle activity. The player knows that some of these drawers will contain useful items and looting a room becomes part of a larger plan.

In Amnesia a lot of the level design worked by having a large puzzle (e.g. starting an elevator) that was solved by completing a set of spread out and often interconnected puzzles. By spreading the puzzles across the rooms, the player needs to always consider where to go next. It’s not possible to just go with a simple “make sure I visit all locations” algorithm to progress through the game. Instead you need to think about what parts of the hub-structure you need to go back to, and what puzzles there are left to solve. This wasn’t very complicated, but it was enough to provide a sense of planning.

SOMA has none of these features, and none of its additional features make up for the loss of planning. This meant that the game overall has this sense of having less gameplay, and for some players this meant the game slipped into walking simulator territory. Had we known about the importance of the ability to plan, we could have done something to fix this.

I put in bold the two statements I thought stood out the most. The first one is regarding the reception of SOMA in the context of Amnesia. A common complaint Frictional saw levied against SOMA was that it was too much of a walking simulator. An interesting complaint, one that I can understand to some degree, but at the end of the day seems to be an oversimplification. It’s like complaining that a really great margherita pizza is just bread and tomatoes… you’re not wrong but you’re also missing the point.

This section goes on to explain the mechanics that kept Amnesia out of the walking simulator category. The sanity system, light and health management, and the puzzles added layers of planning for the player to engage in. SOMA had none of these features and didn’t make up for it, this is the second statement I put in bold. While I completely agree with this assessment, why does SOMA feel just as engaging to me? Actually, upon repeat playthroughs of both games, SOMA stood out more, I mean I’m writing this whole article about it and not Amnesia for instance.

My conclusion is that SOMA’s minimalist gameplay pushes to the forefront its true strengths: the narrative, environmental storytelling, compelling player choices, and an immersive, detailed world. In the past, Frictional have equated their game systems approach to sensory deprivation. Limit what systems the player can engage with to amplify the horror. By turning your focus elsewhere the player is more likely to imagine what the noise around the corner might mean. What keeps SOMA away from walking sim territory for me is how the game sparks your imagination, feeding you the right amount of information and revealing the narrative at just the right pace. This all stems from exploring the different PATHOS-II sites, learning the stories hidden there, navigating foreign and dangerous situations, and pushing forward. The pacing is absolutely tied to that sense of progression just as much as actually traversing to the new areas.

One more thing on SOMA’s minimalist gameplay, note the comment I screenshotted below. It was in response to the above blog post and got me thinking about the feeling of not having much to do in SOMA. There’s not much to acquire, no inventory to manage, etc. Would SOMA have benefited from having battery packs for your flashlight lying about the world? Medkits in drawers? I don’t think so, not if I understand the goals of the developers correctly. And I think I’m a decent playtester to make this statement. Like I said, I’m not generally motivated to play games because of their narrative. FTL is my favorite game of all time, I’ll make a little narrative through my gameplay choices if I want. I just raved about Amnesia: The Bunker, check it out, I didn’t mention the narrative once. I just loved the gameplay systems going on in The Bunker and was too caught up in those to look further into any narrative. SOMA on the other hand gives you no choice, either embrace the environments, the narrative, the existential dread or you’re not getting much out of the experience. I admire the dedication to the narrative, I admire the commitment to go all in on a concept, I admire the restraint to not mechanically make an Amnesia: The Dark Descent 2.

With all that being said, I can totally understand someone who’s not immersed in the story getting absolutely nothing out of SOMA. Not all games are made for everyone and developers shouldn’t even try going down that path. Taking risks grants the possibility for great games. Ok, that’s enough on progression, planning, player goals, etc… for now. Let’s get out the Dive Room and explore Omicron, we have a corpse to repurpose.

Site Omicron - Why Rollercoasters Don’t Make for Engaging Games

Timestamp - 10:26

With Catherine’s help we now have access to some terminals and are able to override the quarantine lockdown. This opens the shutters on a bunch of doors, giving us access to new areas of Omicron. At this point, there is no clear direction for us to go for forward progression. But we’re still contained to this small site, so there’s a manageable number of rooms and areas to explore.

Multiple times throughout Simon’s journey, the larger PATHOS-II sites allow for a small amount of ambiguity when it comes to the direct path forward. You’ll be given a task and there will be multiple areas to explore that may contain what is necessary to proceed. This gets into player agency which is the subject of another article written by Thomas Grip: 9 Years, 9 Lessons on Horror. The excerpt below details an aspect of horror game design that is very key.

Lesson 9: Agency is crucial

When I talk about agency, I’m not talking about the CIA. What I mean is agency of the free will kind. A game that has a lot of agency lets the players make decisions and feel like an active part of the narrative.

This is closely tied to the previous lesson. Not only do we want to give players a role, we also want them to own that role. They need to feel like they really inhabit the character they are supposed to play. A game can achieve a lot by combining agency with keeping things vague – and letting players decide to take uncertain decisions.

Say that you are faced with a dark tunnel – dark tunnels are pretty scary!

Now imagine that the game explicitly tells you that your goal lies beyond the tunnel. There’s no choice, you gotta go in. And if the game forces you do something, it will also make sure you do actually have the means to complete this quest – in this case get to the other side of the tunnel.

But what if entering this dark tunnel was voluntary, or at least presented as such? The game vaguely tells you that there might be something important there – but you don’t know, and might also be a certain death. All of a sudden the tunnel feels a lot less safe. By adding agency and making entering the tunnel an uncertain choice, all sorts of doubts pop up in the player’s mind.

I think this is where Amnesia: Rebirth ultimately failed for me. The game felt like one big rollercoaster, entertaining at a surface level initially then fading to exhaustion. I, the player, had zero agency. And another key component to a rollercoaster is that at the end of the day you don’t go anywhere. Rebirth has an awful sense of progression. Dangling the carrot of reaching an unknown town, so that you can speak with a doctor you barely know, about your mysterious affliction you hardly care about because you’re indestructible is such nonsense compared to what SOMA accomplished… But I digress, let’s stay focused on SOMA.

So now we have choices on how to proceed, where to first? The cleanroom, robot repair bay, mess hall, power room, hydroponics, the laboratory? The uncertainty plus player agency is the potent concoction that drives the tension and keeps the player in control and engaged. The game is confident enough in itself to allow the player to control the pacing. It doesn’t rely on shocking jumpscares or cheap redirections to trick the player into feeling fear. It lets the established atmosphere simmer and knows tension will build.

In the following sections I will detail the various things that can appear/happen/be found in these rooms during our exploration.

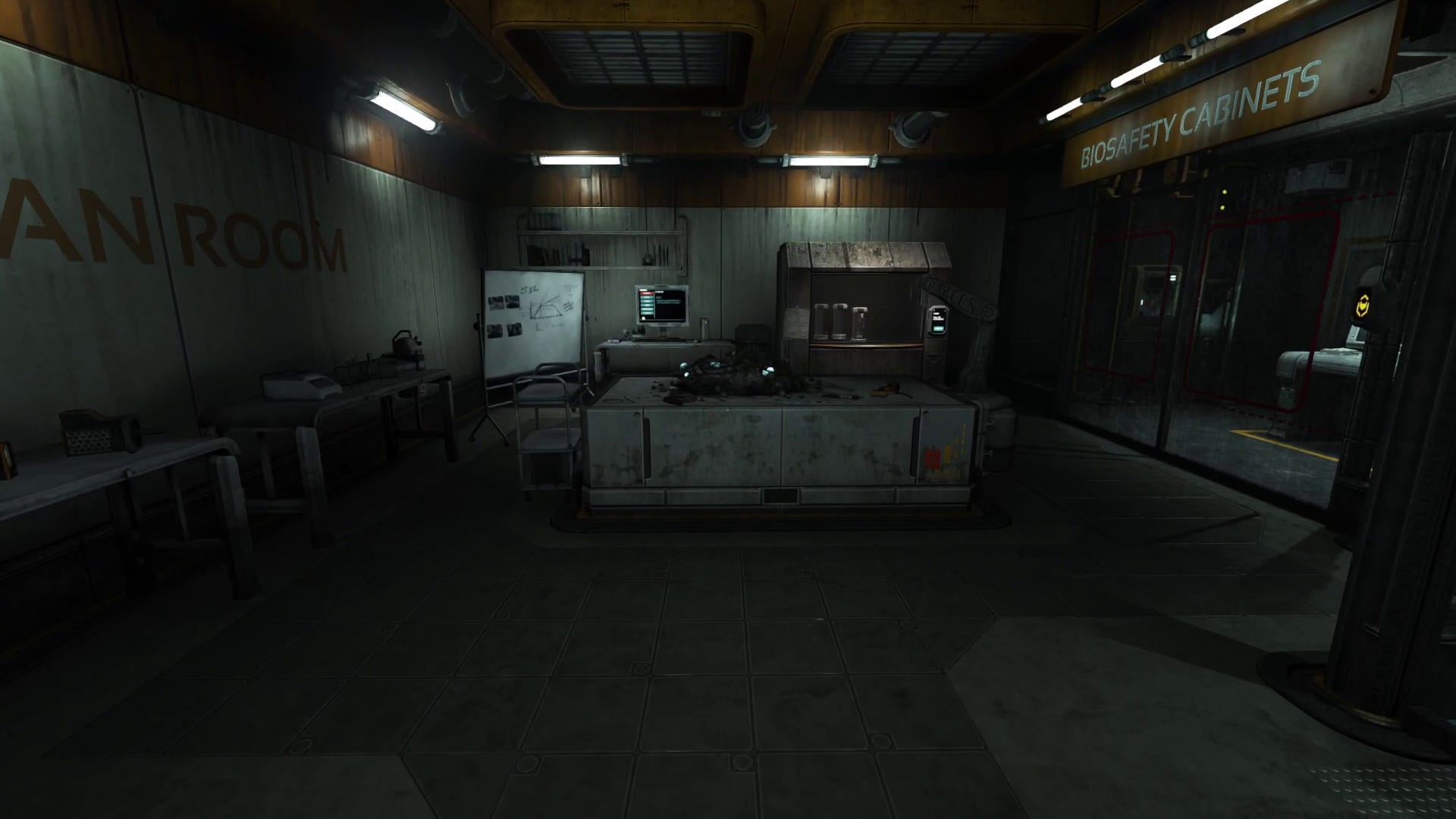

Various rooms found throughout Omicron.

The Laboratory - Engaging Environmental Interactions and Lite Puzzles

Timestamp - 11:58

In our exploration of Omicron we come across a clean room where scientists were conducting experiments on the structure gel. This lab demonstrates a common trait found in Frictional’s games: engaging environmental interactions. Frictional likes to use the physical setting, their physics engine, environmental clues, and interactable objects to put together these “puzzles”. I say “puzzles” because they’re very lite puzzles. While calling SOMA’s puzzles lite may come off as a critique, I think it’s a strength of the game.

The puzzles in SOMA are mostly very immersive and try to make as much sense as they can. I say that because, I think first and foremost, the developers wanted the puzzles to be seamless in their environments. Puzzles can quickly stick out like a sore thumb if they’re thought of first then plopped into a setting. So, if we take the clean room puzzle as an example, it combines interacting with a robotic arm/structure gel dispenser, testing structure gel out on test subjects, fixing a chip for a fume hood, reading some lab notes about structure gel, and piecing it all together. You can certainly brute force your way through it, but if you take your time, you can appreciate the detail and logical sense these types of interactions make. For instance, if you read the lab notes the scientists mention how the gel can help reconstruct microelectronics, the whiteboard has photos posted with images showing their experiments, in the load lock someone was already working on a circuit board similar to the one you pulled out of the fume hood. All of this stuff hints at the direction you need to go and are things that Simon’s (your own) brain can handle while being set very sensibly in the technical environment we find ourselves in. It dumbs down things just enough to be digestible, but not too much to where you’re just putting the square peg in the square hole.

Dispatcher Room - Environmental Storytelling

Timestamp - 26:24

An eerie silence extends across Omicron. Dead staff and their blackboxes no longer hold answers as to what led to their demise. What happened here at Omicron is a question that permeates the atmosphere of this site. Faces and stories remain shrouded in mystery but through careful exploration a couple names begin repeating: Dr. Johan Ross, Raleigh Herber, and Julia Dahl. This is uncovered through laboratory notes, logs on computer terminals, dispatcher calls, audio logs, plus environmental clues. For instance, we actually “met” Herber very early on, she’s the body inside the power suit in the dive room we’re trying to repurpose. What was she trying to do with that power suit? Herber is also the dispatcher for Site Omicron, so the room we’re examining in this section is relevant to her specifically.

As we approach the room, we see a body slumped against the wall, curiously with its head still intact. Upon closer examination, the internals of whatever this is are at least partially mechanical in nature. Sitting in a pool of what appears to be structure gel, I’m led to think this is a life form spliced together by the WAU in its attempts to preserve life. Moving inside the dispatcher room, three areas of interest become readily apparent: there’s an accessible computer terminal, a WAU growth too close to the desk, and some cryptic scribblings on the white board.

Accessing the computer terminal, we’re able to replay the last couple calls ingoing and outgoing to and from Omicron dispatch. Here we can listen in on the last call from the Ark Team as they descend into the abyss. We now know they at least made it out of Omicron safely. The following calls to Tau and Phi go unanswered as it seems Raleigh is concerned about the Ark Teams status. They missed the scheduled pickup 2 days after their descent. The final call comes a couple weeks later, and it seems Raleigh is letting her fellow dispatcher at Theta know she’s making an important trip and may not be around for a while. Hence why we see her in the dive room with a power suit on. But why is she going to the abyss?

The next observation is more minor but could have some bigger implications. Why is there WAU mind coral so close to where Herber would have been sitting? I bring this up because other than of the central containment chamber, which is completely overrun within visible structure gel growths, the WAU is not very visibly present throughout the rest of Omicron. We know through audio logs found earlier that the WAU was trying to resurrect Johan Ross by transmitting electromagnetic waves through the containment chamber. Was the WAU trying to manipulate Herber as well? But wait, we also heard earlier that Ross was speaking to Herber telepathically, does the mind coral in close proximity have anything to do with that?

The last observation we can make is about the obsessive scribbles and notes found on the desk and white board. These notes further reveal that Ross was certainly trying to influence Herber to go to Site Alpha and destroy the WAU. It seems as though Ross was even putting images into her head. Herber isn’t even sure Alpha exists, yet she’s still sketching out the renditions of the WAU on notepads. So why is the WAU resurrecting Ross? Is it just the WAU’s standard procedure to preserve life, or something more?

I’m not going to answer the questions that this room purposes, mainly because I don’t have most of the answers, but also because it’s fun to try to come to your own conclusions. Maybe I’m even asking the wrong questions? But I hope this section at least demonstrates some of the trains-of-thought that SOMA’s environments stimulate.

Power Room - Unique Monster Design

Timestamp - 36:18

Through this article so far, I’ve discussed several topics: player immersion and agency, storytelling, puzzles, the environments, the setting, but I haven’t directly talked about what makes SOMA scary or why it’s a horror game. Part of the reason is because all the pieces listed above are pieces of the horror puzzle in both direct and indirect ways. I think a huge strength of SOMA’s is that it takes itself very seriously. All those pieces are intricately detailed, thought-provoking, and immersive. I hope the previous sections of this article demonstrated that; so, when it comes time to discuss the more traditional horror elements, we all know the strength of the game’s foundation.

In our exploration of Omicron thus far, we have only seen the results of horrific things that took place. We’ve been piecing together what exactly occurred here at Omicron and trying to gather together key parts needed to use the power suit. I’d describe these segments of gameplay as a tense and immersive experience, not overtly horrific. These exploration segments and even more so your times with Catherine, serve as a lull in the horror, a breather from feeling alone. The exploration contributes more to the rise in tension. While you may not be directly under threat, you’re never quite sure what’s going to be around the next corner. Additionally, when the game opens up and allows the player to pursue multiple avenues, your mind starts to wander. Should I go this way? Is this the right way to go? Am I only putting myself at risk venturing into this area? Where exactly is what I need? The uncertainty adds to the tension.

Our search for some sort of power source for the suit leads us to the Omicron’s power room and here we encounter another lifeform. SOMA intentionally implements slight tonal shifts in the lead up to monster encounters. This is important because there’s a wide range of lifeforms still on PATHOS-II and their intentions and capabilities aren’t necessarily clear. Here, as we move towards the back of the power room, we hear raspy, irregular breathing. Is there danger or is someone just lying on the ground, being kept half-alive by the WAU? As we approach, something shakes the entire station causing the lighting to shut off in the section. The eerie ambiance swells and every fiber of your being is sounding off alarm bells, you are in danger!

As we move closer, the previously far-off irregular breathing turns to exacerbated sobbing and moaning. The lifeform seems completely stationary, transfixed in a corner of the room. Then the developers play a funny trick… Crossing into the back of the room there’s a chokepoint that is partially blocked on the right by a table and some assorted debris on the left. The tricky part is that there’s a medium-sized, metallic bin precariously placed on the edge of the table. I feel like most players here will focus on the scattered debris on the left, making sure to skirt around whatever exactly it is. Meanwhile, they bump into the unexpectedly protruding bin on the right. I speak from experience. Bumping into that bin causes quite the commotion, a commotion that the creature is not awfully fond of. The sound triggers the creature as it lights up and screams horrifically. This is your warning shot, communicating to the player that sound aggravates whatever this thing is. As we slowly and quietly skirt around the room we notice objects scattered around. They’re mundane objects, pipes, buckets, and such, but in this context, they act like a mines in a minefield you have to navigate.

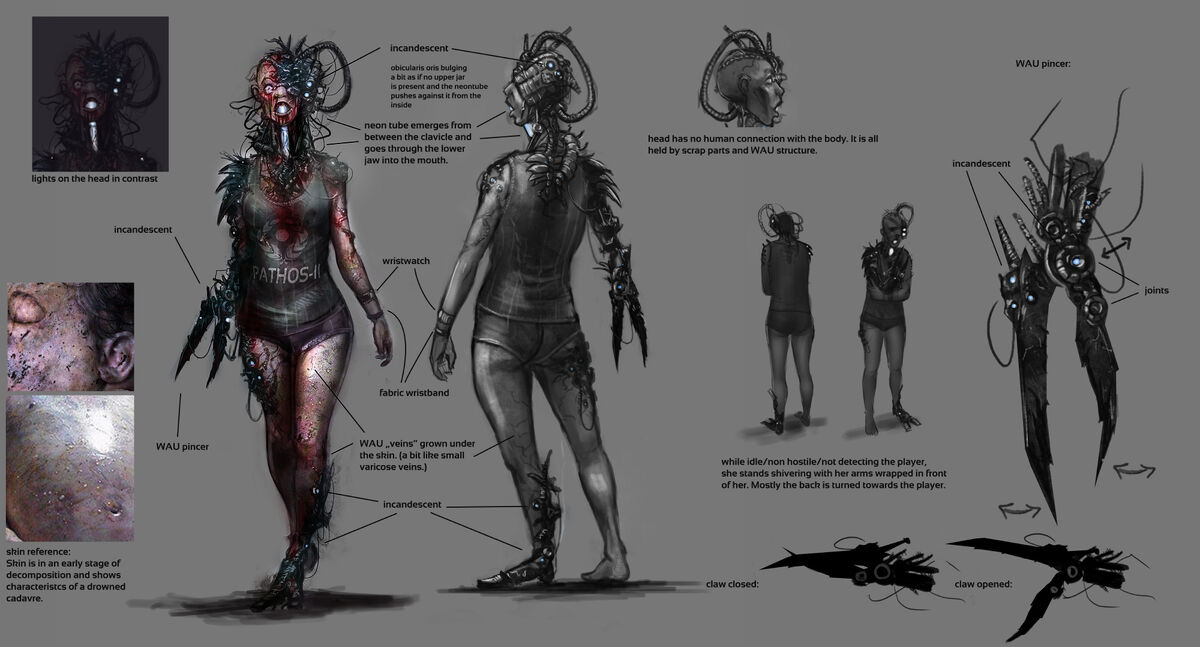

While most monsters in the game are sensitive to sound. The robot girl amps that up to eleven by being extremely sensitive to it, balancing out the fact that she’s typically completely stationary. The consequences for aggravating her are also more decisive. In previous playthroughs when I slipped up, I was never able to escape her. These mechanical distinctions, plus her visual design encapsulate the effort Frictional put into designing unique monsters and thus keeping the player fearing the unknown.

To expand a little more on how each lifeform on PATHOS-II behaves uniquely… I believe this is due to the vastly different ways these lifeforms are experiencing the post-apocalypse. Whether it’s a deranged monster or a helpless robot, how they personally view their current situation is hard to interpret. In real life, humans often can share a lot of common ground, leading to us being able to interpret and assume things about others. This isn’t always a great thing, our assumptions are often based on stereotypes and people fitting certain molds, but it’s something our brain does to simplify and understand the world around us. We know lifeforms in SOMA aren’t so easily put in a box because in the game we get to meet many lifeforms that demonstrate different understandings of what’s occurring right then, in that moment. We know for a fact many lifeforms also experience reality very differently. What I’m getting at, is that these ideas can feed back into that fear of the unknown and potentially opened up doors for the developers while designing these monsters. What happens when a human consciousness doesn’t experience sleep? can’t move whatever vessel they’re in? is hooked up to some overly sensitive audio receptors? doesn’t exist in continuity with time? can move but can’t communicate by any traditional means? Talk about some horrific questions! Talk about ways to become sympathetic with the monsters that haunt you!

The Dive Room Part 2 - Player Choice Done Differently

Timestamp - 40:33

When a player hears the words ‘player choice’ tossed around or when a game advertises itself with the phrase ‘your choices matter’ I think most players automatically know sort of what to expect. We’re very used to narrative consequences where you choose a certain dialogue option or kill a particular NPC and the plot and characters adapt to that choice. RPGs for a long time have done the ending slideshow, illustrating the impact you had on the world and its factions. Player choice can sometimes reference gameplay options available to the player. Do I take the stealthy approach or go in guns-blazing? SOMA doesn’t really have or emphasize any of this. Simply put, how SOMA implements player choice and consequence is veerrryyyy different. To setup the choice present here at Site Omicron I’m going to have to go through a bit of background and describe the full context, so bear with me here.

So, after sneaking past the crying robo-girl and grabbing a power suit battery, we return to the dive room. We tell Catherine we found the parts and talk for a bit. In our conversations with Catherine since switching to plan B with the power suit, she has been misleading on how we’re actually going use said power suit. Initially, when you hear about finding a power suit, you first imagine putting it on, as any human would. Then you realize you’re already in a diving suit, so how would that work, can I even take this suit off? Catherine suggests, well maybe we’ll just have to do a transfer. Transfer is the key word here. It implies continuity. We’ll get into why this is sensitive, but if you take in the full context of Catherine’s situation, it’s hard to blame her because Simon is all she has. If being tactful means she accomplishes her objective, then you can see why she leads him on.

If you recall all the way back at the start of this article, I introduced SOMA and our protagonist, Simon. I briefly noted that as we took over as Simon at the start of the game, we had to go in for a brain scan. For more context, Simon was in a car accident and suffered a severe head injury and was given months to live. This led him to search out alternative solutions. The brain scan was setup and performed by a PhD student - comp. sci. duo, David Munshi and Paul Berg, whose interests were in brain reconstruction and artificial intelligence. As soon as the brain scan commences, BOOM, Simon and the player are transported to the future and to the bottom of the ocean. What happened? Well, two things happened: first, the brain scan made a copy of Simon’s conscience and saved it to Munshi and Berg’s computer, then well into the future in PATHOS-II, someone or something loaded Simon’s brain scan into the diving suit he’s currently walking around in. The important note here is that the game only shows you one branch of the now copied Simon brain scan. One of those branches is the brain scan ending and Simon standing up and leaving the office. But that is now just one continuity in a sea of potential continuities for Simon.

This brain scan is not only an incredibly important moment for Simon but also for humankind. With the fortune of hindsight, observations made during our time at PATHOS-II tell us that our brain scan and the research that Munshi and Berg were performing was foundational for current brain scan technology. The position that our current Simon is in is made unique by the simple fact that the technology itself allowed a version of Simon to bypass a huge chunk of time. More significantly, a time when brain scan technology would have developed both technically and in the collective conscience of society. Simon has no context for what social norms exist regarding brain scans. He has no knowledge of ethical standards that may have been established regarding this technology. Simon is us. We also have little context for these existential questions either. This makes Simon more than a character we just move around on a screen. The reality of this Simon is inherently tied to who we are as humans right now.

So, getting back to Omicron, we still have to transfer to the power suit. We patch up the power suit with the components we’ve collected and move to the pilot seat, a setup looking pretty similar to the one in Munshi’s lab… Catherine starts the scan aannndd BOOM, we’re in the power suit. Nice, it worked. But then reality sets in, you briefly hear a voice across the room say:

“There must be something wrong. Can’t you run a diagnosis or something? Catherine…”

This moment is why Catherine using the word transfer is a bit misleading. What just happened was in some ways, similar to when Simon awoke in PATHOS-II. The game intentionally shifts Simon’s, from Toronto to PATHOS-II, from the diving suit to the power suit. Except this time, there was no time lost between the brain scan and the boot-up of the next Simon. This situation wonderfully and horrifyingly questions your perception of who the “true” Simon is. Is your sense of self tied to who you are physically? You could get away with smoothing over the details back at Upsilon, but now this is right in your face, you just heard yourself from across the room…

Simon is shocked and disturbed by what he just heard. Catherine realizes she messed up by not shutting down the other Simon quicker and is also incredibly annoyed with Simon getting hung up on what she seems to think are small technicalities. The frustration with each other spills over, resulting in Catherine disconnecting, leaving the fate of your former self in your hands. Do you leave Omicron, allowing Simon to awake again, this time alone and with no objective, locked in the dive room? Or do you shut Simon down permanently by erasing his data? This is the choice.

This is one example of how SOMA does player choice differently. In the context of other games, it’s unique because it has no bearing on your immediate objective. You’re in the power suit, the abyss climber is outside the pressure lock, ready to go. By reframing the means by which you arrived in PATHOS-II in the first place, SOMA’s choices poke and prod the players concept of self. What does it mean to be human or robot or both? How do you value artificial intelligence as a lifeform? Should you mourn the passing of your former self even if it was just a brain scan copied onto a computer chip and stuck on a corpse? Is someone’s brain scan just a file on someone’s hard drive? Can we take that file and copy-paste, open up, close out, move to recycle bin all at our own discretion? Can a person even be transferred to a digital format or are we intrinsically linked to our human bodies?

SOMA brings up so many interesting questions that I had never thought of before. And even the ones I had thought of, SOMA shook my position on. To be frank, this section gets into subject matter and qualities of SOMA that are really hard to describe. Just like you may think your existence is tied to your physical nature, SOMA is intrinsically tied to the video game format. Hearing someone describe it or watching someone play it doesn’t do it justice in the slightest. The questions I listed above become more difficult and enveloping when you are in the game world and not a distance third-party, it’s part of the beauty of this game.

The Departure - Into the Abyss

Timestamp - 45:58

Not much to say here except that the ocean both terrifies and fascinates me, and this sequence captures that duality perfectly.

The unknowable vastness of the abyss…

The inescapable fact that humans do not belong here…

The unimaginable pressure…

Despite this, we continue on.

The Wrap-up

That is all for the video and that is all for the breakdown of Site Omicron. I set out with the intention to investigate gameplay and story elements found at Omicron as sort of a representative sample for SOMA. Through the investigation, I wanted to figure out and capture why I find SOMA so engaging despite its minimal amount of gameplay systems. I think, with the previous sections as evidence, I’ve accomplished this. To be sure and simply recap, let’s do a quick rundown of the main points in no particular order:

Frictional established a detailed, believable world. The facility, PATHOS-II, feels like a real place that could exist in the future. Many PATHOS-II staff members have fleshed-out backstories. Plus, we can investigate their fates as it relates to the fall of PATHOS-II.

Key plot points and the communication of objectives occur during gameplay. SOMA’s ultra-minimalist HUD plus zero use of menus or cutscenes means everything occurs and can be understood while in the first-person perspective.

Monster design is creative and the encounters are well-paced. Frictional never lets the player get comfortable or familiar with the monster designs. PATHOS-II’s multiple site layout means there’s a natural rise and fall to the tension involved with monster encounters.

Player choice impacts Simon and the player more so than the game-world or narrative. SOMA is a prime example of how to craft a tight narrative while taking advantage of the video games as an interactive medium.

The world/level-design and narrative form an excellent sense of progression. This couples with clear communication of objectives to create a satisfying journey that the player is in control of.

Engaging environmental interactions deepen the players connection with the game world. Frictional has accomplished this with their physics engine and immersive puzzle design, giving environments a tactile element.

AND last but not least… While I didn’t dedicate a section to it since the focus was specifically on Omicron, SOMA’s overarching narrative and themes are fascinating and well explored. Play SOMA, it’s one of the greatest narratives in video games.

The END

If you’ve made it this far, thank you for reading! I appreciate you sticking around and checking out my work. If you want to get notified the next time I publish an article, feel free to subscribe, it’s free. And if I didn’t make it clear already, check out SOMA, it’s quite good. Also, check out Frictional Games’ other games too while you’re at it! Amnesia: The Dark Descent is a certified, horror classic and Amnesia: The Bunker is one of the best modern survival horror games. Until next time…